For those of you who do not know, in late July I traveled to Poland with my father, Dasha (my very good friend who is a Polish Holocaust survivor from my grandmother’s town) and a group of people whose ancestors were from Zaglembie. Zaglembie is a region in the Katowitch county in Southern Poland about an hour from Krakow and includes towns such as Będzin, Sosnowiec, Dabrowa Górnicza, Czeladź, and many others. The region is rich with coal mines, which is why the area is called Zaglembie, meaning “from the depth.” There were about 100,000 Jews living in Zaglembie area at the start of World War II. At the turn of the 20th century, half the citizens in Bedzin were Jews. My grandmother, as well as Dasha, was from Bedzin. Our trip was as follows: Krakow for Shabbat, Auschwitz on Sunday, Zaglembie (Bedzin, Czeladz, and surrounding areas) from Monday to Thursday, Sochocin (my father and I visited my grandfather’s town) on Friday, and Warsaw for Shabbat. My father and Dasha left Poland on Sunday and I stayed until Wednesday for a genealogy conference. I kept a journal during the trip and sent them out as emails to friends and family. As a birthday present for my father (and in honor of International Holocaust Remembrance Day), I promised him that I would post my last journal entry on Facebook.

(Comments in bold italics are from my father)

Shabbat: Warsaw

We had a nice Shabbat in Warsaw. We davened at the Nozyk Synagogue where Dasha said hello to her very good friend Rabbi Michael Schudrich, the Chief Rabbi of Poland. Dasha used to come to Poland in the 90’s to work in his summer camp for Polish Jewish children. We even met a young man who went to that camp as a kid. After davening, Dasha introduced us to Rabbi Schudrich and told him that my father’s great-great grandfather was the last chief rabbi of Warsaw. He was very nice but was a bit distracted by all the people coming up to him. We walked a few blocks to the Galil Restaurant where we had both Friday night dinner and Shabbat lunch.

Walking around Warsaw was extremely weird for me. Most of my grandmother’s stories were from Warsaw/Warsaw Ghetto and you can’t see any of that history there today. Between 85-90% of Warsaw was completely destroyed during the war so it had to be completely rebuilt. Even though I had exact addresses for where my grandmother, her sister, and her in-laws lived, those places don’t exist anymore. The streets aren’t even the same. This caused Warsaw to feel very foreign to me. Especially coming from Krakow and Bedzin where almost nothing has changed. I honestly expected Warsaw to look like Krakow’s Jewish Quarter but instead it’s a completely modern city, with a few Soviet-era buildings. Extremely ugly Soviet-era buildings.

My dad and Dasha’s flight was at 10am Sunday morning, which meant that they wouldn’t be able do any touring that day. There were two options to see the POLIN Museum. Either on Saturday with the non-observant people in the group, or on Sunday morning. My dad was really determined to see the POLIN Museum. That was the one thing on the trip that he was set on and he said he wouldn’t leave Poland without going.

Friday Night, the crowd at the Nozyk Synagogue was standing room only. Many of the folks came from overseas (mostly Israel and the US and every other major country) for the Jewish Genealogical Conference, which would begin the following week. Our group alone was 150 strong. Add to the crowd the heat - it was 100 degrees Fahrenheit in the shul at night. Lastly, they had turned on these huge metal fans to circulate the air - unfortunately, they were extremely noisy and you could barely hear the chazzan.

We asked around and were told that besides the metal detectors, the museum itself was not too interactive (meaning that there are things you can touch that are interactive but you don’t need to) and doesn’t have motion-sensors.

I felt that after the Friday night shul experience I’d rather pray by myself in the room early Saturday morning and join the group at the POLIN museum. David, the Israeli tour guide, was nice enough to lead a separate walking group from the hotel to the museum for those who don’t travel on Shabbat (15-20 folks had the same idea). I heard many good things about the POLIN museum (basically a 1,000-year history of the Jews in Poland) and it was ranked the #1 museum in all of Europe in the last few years (it opened in 2014. Dasha was at the opening). I wish I could have spent 1-2 days in the museum instead of 3-4 hours on Shabbat. Some of the exhibits are interactive so I had to observe others and missed hands-on experience. It was truly an amazing and informative experience. I felt that after the Friday night shul experience I’d rather pray by myself in the room early Saturday morning and join the group at the POLIN museum. David, the Israeli tour guide, was nice enough to lead a separate walking group from the hotel to the museum for those who don’t travel on Shabbat (15-20 folks had the same idea). I heard many good things about the POLIN museum (basically a 1,000-year history of the Jews in Poland) and it was ranked the #1 museum in all of Europe in the last few years (it opened in 2014. Dasha was at the opening). I wish I could have spent 1-2 days in the museum instead of 3-4 hours on Shabbat. Some of the exhibits are interactive so I had to observe others and missed hands-on experience. It was truly an amazing and informative experience.

It was always fascinating to listen to David point out places of interest as we walked to and from the museum. We explored the area where the Warsaw ghetto wall used to stand (there is a gold line running through the streets of Warsaw showing the demarcation line). We had a museum guide but David led the tour in the museum and the museum guide filled in some details along the way. It was interesting to note that Poland was the second country in the world to have a constitution after the US and at one point there were 9 members of Parliament that were Jews (including Hasidim). In 1919, Roza Pomerantz-Melzer, a member of a Zionist party, was the first woman elected to the Polish parliament. Fascinating to learn about the vibrancy and depth of Jewish culture in the 19-20th century, including 15-20 daily Jewish newspapers, plays, writers, etc. Most of my life I have viewed Polish Jewry through a religious lens - yeshivas, synagogues, rabbis, and their oeuvre. It is limited and only a sliver of the real picture of Polish Jewry that was and never will be again in my lifetime. Not enough time for me to absorb and retain the details of my visit. I hope to visit again with Hindy sometime in the future.

They walked back to the restaurant and joined us for lunch. Dasha didn’t join us for lunch. She stayed in the hotel and was visited by her friend Ewa. They walked over to Ewa’s mother’s home to visit her and she said she had a very nice time.

In the afternoon we met up with Jeff and Helene Morrison from Melbourne, Australia. I’m friends with their son who lives near me in Jerusalem. They were two of the few shomer shabbat people so we stuck together. Along with Josef and Amira Skoczylas (who are my friend Michal (Wrotslavsky) Goldstein’s sister’s parents-in-law), we made our own walking tour of Warsaw, with Jeff leading as tour guide. Jeff was very knowledgeable on our walk.

We saw some of the remnants of the Warsaw Ghetto walls and the “Footbridge of Memory,” which is a memorial of the footbridge which connected the small and large ghettos at Chłodna Street. While standing on the former bridge one would be able to see the free “Aryan Warsaw” below them. The footbridge became one of the symbols of the Warsaw Ghetto and the monument was constructed in 2011. The installation is made of two pairs of metal poles connected at the top with optical fiber cables that light up after sunset and project the shape of the footbridge. Since it was still daytime we weren’t able to see it lit up but at the base of the poles were viewfinders where you can flip through images of life in the ghetto and in Warsaw during the war.

After Shabbat, the Morrison’s, Dasha, my dad, and I went to an ice cream shop recommended by Natanel, a boy in the group who said he had found “the best ice cream in Warsaw” but couldn’t come with us in the end because he had a fever. And it was really good ice cream. Dasha was happy to join us and get out of the hotel for an excursion. We went back to the hotel and found a small group of people reflecting on the trip because Rina was asking for feedback. We joined for a little bit but then Dasha broke it up because someone was talking too much and she said that he would “go on for hours” if no one stopped him.

The man was telling us his story and why he joined our trip. I forgot many of the details of where he is from (I think Germany or somewhere in Europe). His father died and an old friend of his father contacted this man and somehow he found out that his father had been Jewish and born in Poland. It was only a few years prior to this trip and he wanted to connect to the town where his father grew up. There are more details to the story but he was talking and Dasha interrupted him saying there are many stories like this (as in this is nothing new). She felt that he would be going on and on for hours shlepping the story out so she thought it would be better to cut it short.

Since Dasha and my dad were leaving very early in the morning, we said our goodbyes and exchanged contact information. Dasha and I took a picture, which is now one of my favorite pictures of us.

We went upstairs, finished packing, and went to sleep.

Sunday: Conference/Sochocin

We woke up very early because my dad and Dasha needed to get to the airport around 7:30am. I said goodbye to them, gave them both giant hugs, and sent them on their way.

Those of us remaining in Warsaw met in the lobby of the hotel for a walking tour of Warsaw, followed by a tour of the POLIN Museum.

We walked to the remaining ghetto walls and David explained what the ghetto had looked like and its history.

Sources say that at its height, there were 500,000 people in the Warsaw Ghetto with 8,000 people dying weekly. The small ghetto was where the rich lived and the larger ghetto was for the more “middle class” people. After a year, the small ghetto was closed and those occupants were moved to the large ghetto.

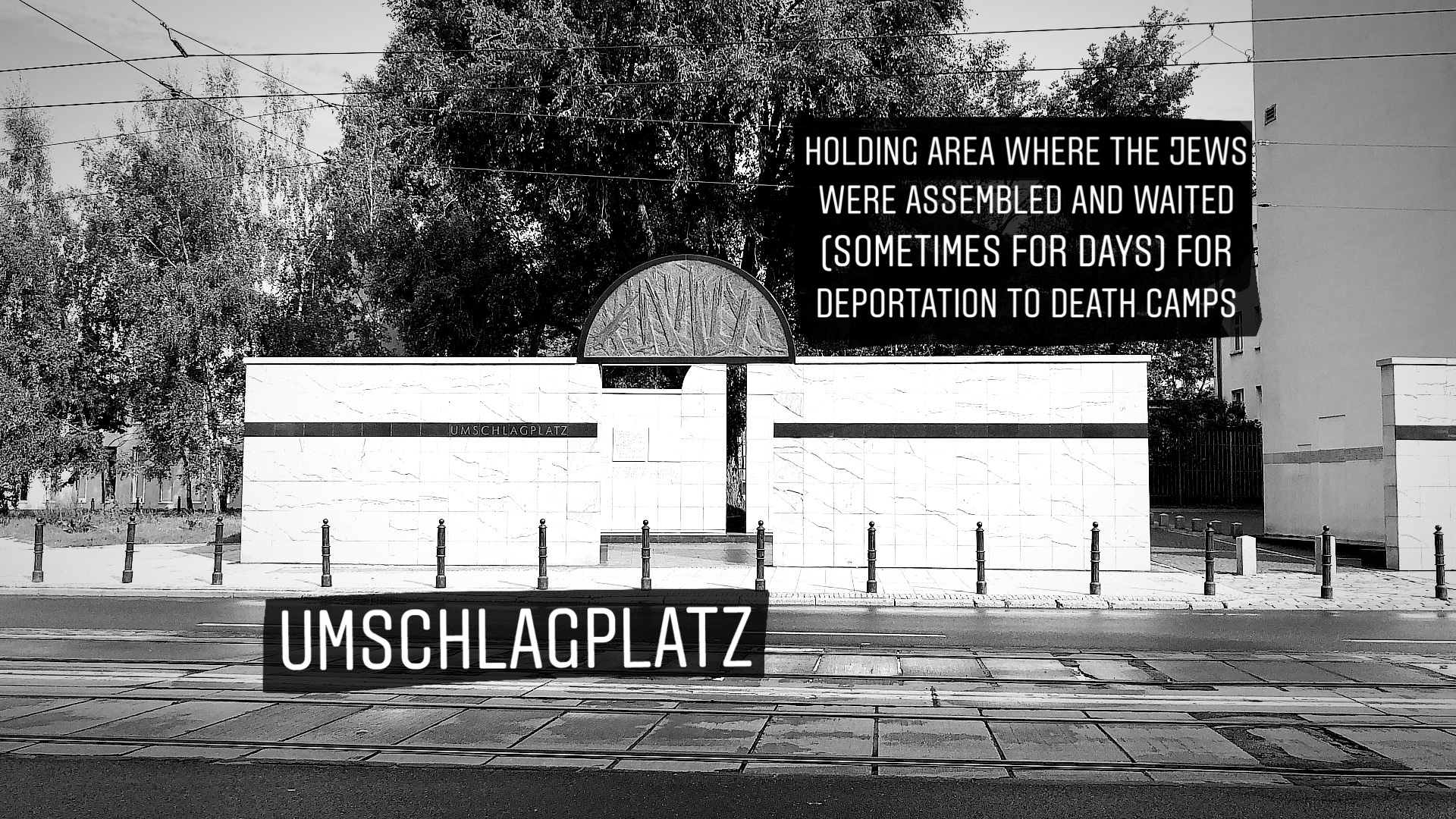

We visited the Umschlagplatz (German for “collection point”), which was a holding area set up by Nazis where the Jews were assembled and held until deportation to death camps.

Many cities had an Umschlagplatz but Warsaw’s was the largest. The Jews were arrested in the ghetto and marched to the Umschlagplatz, where they waited hours, sometimes overnight, for the train to arrive. When the train arrived, they were packed 100-120 people to a cattle car.

In 1988, the stone monument, which resembles an open cattle car, was erected at the Umschlagplatz to commemorate the more than 300,000 Warsaw Jews who were deported to their deaths from that very spot. Although she never mentioned the word Umschlagplatz, my grandmother said that when the Nazis came to her in-laws’ home, they took them to a holding place where they waited for a while, maybe a day, before being sent to Majdanek.

The main walls of the monument are engraved with 400 most common Jewish-Polish first names in alphabetical order.

On the right, the same quote is engraved in three different languages; Hebrew, Yiddish and Polish. David chose three people to read the respective quotes on the wall and another person to read the English translation on his phone. The quote reads: “Earth do not cover my blood, let it cry out on my behalf.” David echoed it: “Earth do not cover my blood and become a place where my screams will be silent.”

Luckily I filmed it so I can quote his powerful speech word for word:

“Do you understand what we’ve been doing this week? That’s exactly what we’ve been doing this week. They’re not here anymore. The places aren’t here anymore. We have made sure that the earth will not cover their blood and that their screams will not be silenced. And yesterday at dinner it was very touching when Dan, the next generation, the third generation, one of the gentleman said to him ‘you know what, we’re handing it over to you now.’ Dan’s wife, I think in Montreal, is pregnant so he came on this trip so he will make sure that his children will not let the earth cover their screams. It is, in my opinion, humble opinion, one of our obligations as being from this nation. By the way, it’s other peoples’ obligation too but I don’t demand it from them. I don’t demand it from Jews either but that’s exactly what we have been doing. Think about it. We have made sure that although you can’t see it, you can’t see them, we don’t let the earth cover their blood nor to silence their screams.”

After his remarks about commandments, I walked next to David and told him about my photo series on the “614th Commandment,” a term coined by German Jewish philosopher Emil Fackenheim. Fackenheim defined it as a commandment that “Jews are forbidden to hand Hitler posthumous victories. They are commanded to survive as Jews lest the Jewish people perish. They are commanded to remember the victims of Auschwitz lest their memory perish. They are forbidden to despair of man and his world, and to escape either into cynicism or otherworldliness, lest they cooperate in delivering the world over to the forces of Auschwitz.” I didn’t remember the entire quote by heart so I paraphrased it for him. Then David said something interesting that really made me think. He looked at me very seriously and said “but Hitler did win.” He went on to clarify that Hitler’s goal in the Final Solution was to eliminate European Jewry and he ultimately succeeded. There are barely any Jews living there today. It’s not necessarily because he murdered all of them, but also because Jews don’t feel comfortable there anymore due to continuing anti-Semitism (and thankfully because we have Israel). It was a very interesting point that I had never thought of. Obviously Hitler didn’t win because he didn’t succeed in eliminating the entire Jewish people and we are still here, but he did achieve his goal of freeing Europe of Jews (for the most part). David said, “of course we can never accept the fact that the Nazis triumphed in their war against the Jews. But if you look at cold numbers, they did.”

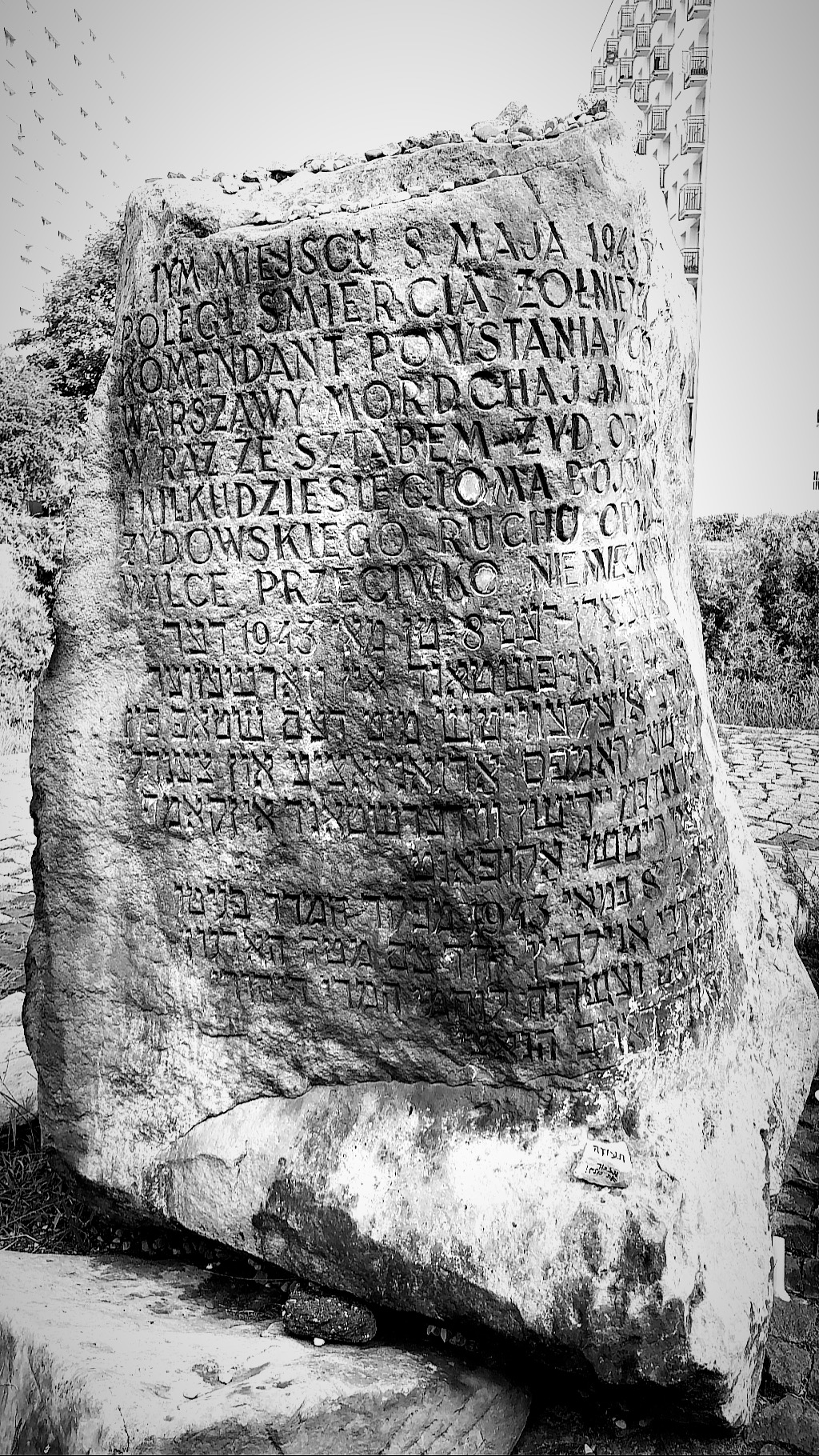

We continued our walking tour to the Miła 18 memorial. Miła 18 was the address of the headquarters bunker of the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB), the Jewish resistance group in the Warsaw Ghetto that led the Uprising. After my grandmother got married in 1938, they were building a home at Miła 44, which was destroyed at the beginning of the war.

In 1946, a monument made of the rubble of Miła houses was erected at the former location of Miła 18. The memorial is known as “Anielewicz Mound,” named after Mordechaj Anielewicz, the leader of the uprising. A commemorative stone was placed on top of the mound with an inscription in Polish, Yiddish, and Hebrew. Many visitors have placed small stones on the memorial, as one does at a Jewish cemetery.

In 2006, an additional monument was added to the memorial.

The inscription is in Polish, English, and Yiddish and it reads:

“Grave of the fighters of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising built from the rubble of Miła Street, one of the liveliest streets of pre-war Jewish Warsaw. These ruins of the bunker at 18 Miła Street are the place of rest of the commanders and fighters of the Jewish Combat Organization, as well as some civilians. Among them lies Mordechaj Anielewicz, the Commander in Chief. On May 8, 1943, surrounded by the Nazis after three weeks of struggle, many perished or took their own lives, refusing to perish at the hands of their enemies. There were several hundred bunkers built in the Ghetto. Found and destroyed by the Nazis, they became graves. They could not save those who sought refuge inside them, yet they remain everlasting symbols of the Warsaw Jews’ will to live. The bunker at Miła Street was the largest in the ghetto. It is the place of rest of over one hundred fighters, only some of whom are known by name. Here they rest, buried as they fell, to remind us that the whole earth is their grave.”

David told us that Israeli Army delegations have big ceremonies here. “I have saluted Mordechaj Anielewicz in the Israeli Army,” meaning that he saluted the memorial, which is Anielewicz’s final resting place.

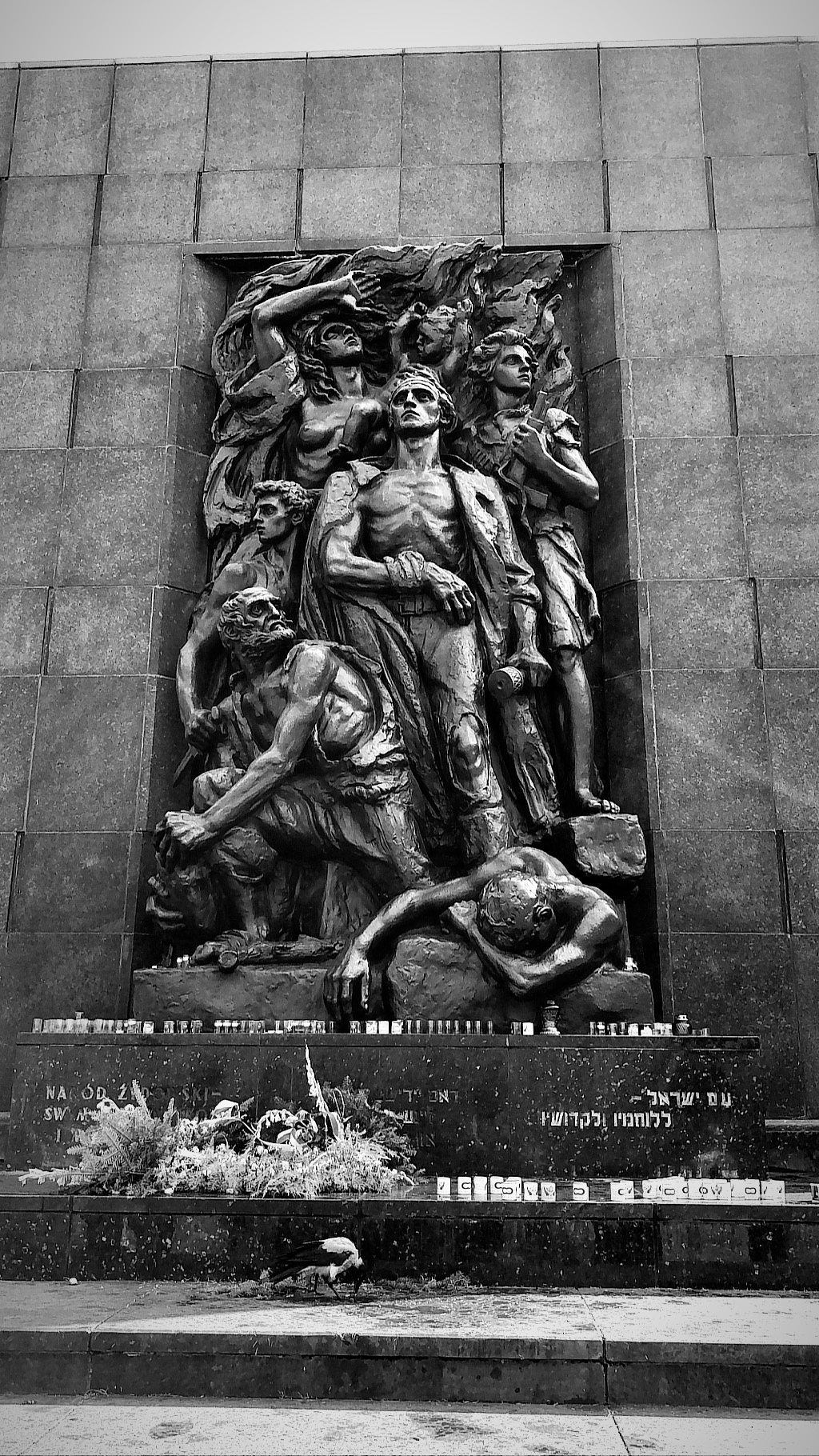

Next, we walked to Rapoport’s Memorial to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, which is right in front of the POLIN Museum. It was created by Nathan Rapoport in 1948 and is two-sided. The wall of the monument looks like the Western Wall (Kotel) in Jerusalem.

One side of the wall has “The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising,” a sculpture of resistance fighters armed with weapons and led by Anielewicz.

The other side shows “The Last March” with men, women and children being led to their deaths.

As opposed to the back-to-back original in Warsaw, the Yad Vashem version of this memorial has these monuments side by side. Yad Vashem wanted to make sure that the warrior side did not overshadow the persecuted side. In one memorial they show both physical and spiritual resistance. Quoting Yad Vashem’s website, “In 1948, spiritual resistance took a back seat to armed resistance. Today, 70 years later, in the state of Israel at Yad Vashem, they can complement each other, side by side.”

In front of the monument, Rina spoke about her father who stayed in the Bedzin Ghetto after the major deportation. He was later sent to Auschwitz and was tattooed with the number 172008. Added up, his number is 18. The number for chai (life). He said, “I shall live.” We sang Am Yisrael Chai.

After that, those of us who hadn’t been to the POLIN Museum on Shabbat went with David, while the rest returned to the hotel with Monika, our other tour guide. While saying goodbye to Monika, I told her that I was hoping to visit the archives in Mława and she told me I need to bring a translator with me. Unfortunately, she was going away on vacation the next day so she recommended her friend Marek and gave me his contact information.

David was an unbelievable guide. There was so much to see in the museum and he was a fountain of information, while also making the tour fun and interesting.

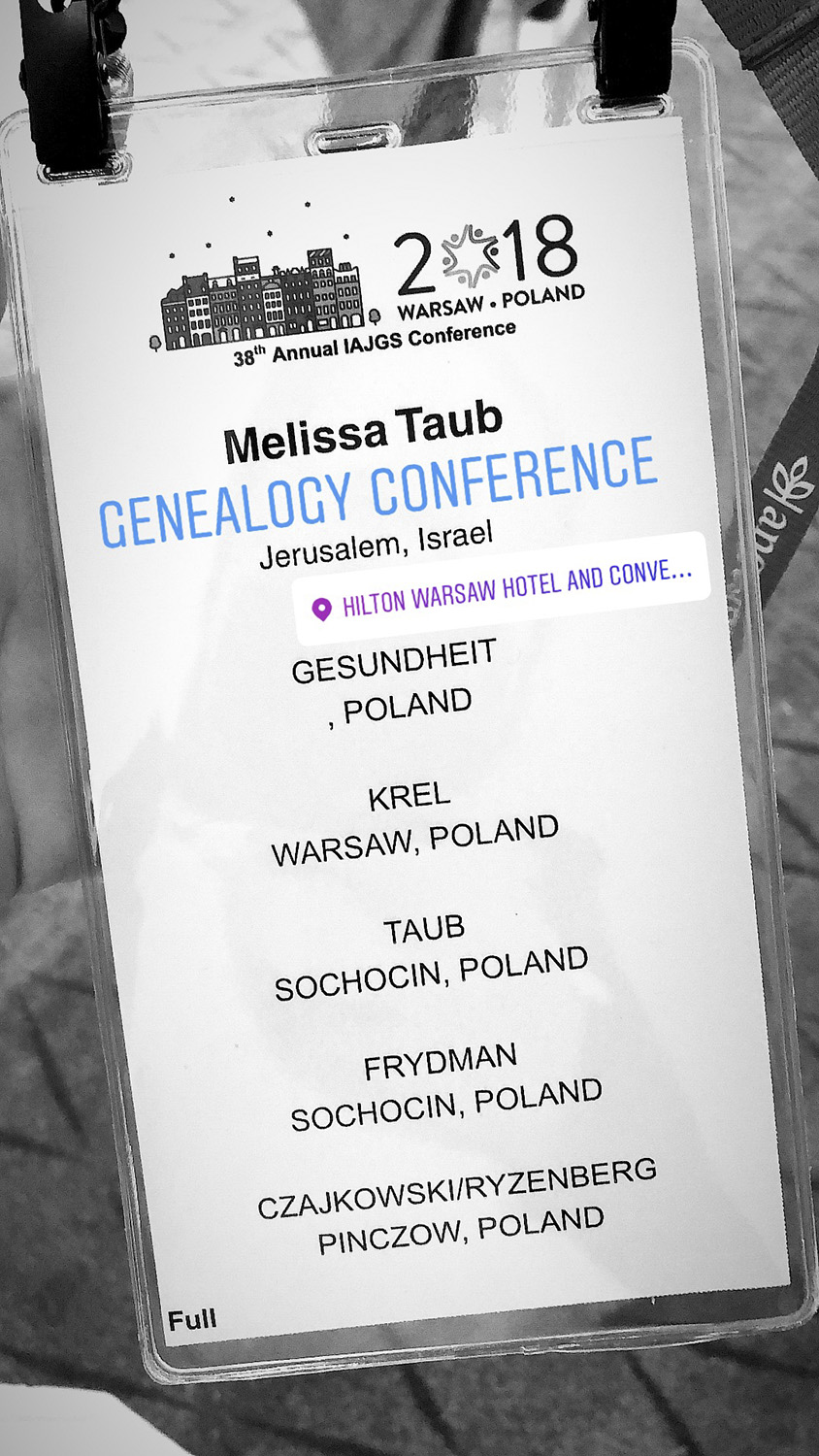

I called Marek and scheduled for us to meet in the hotel lobby on Tuesday morning at 9:30am. I headed to the genealogy conference to check in and look around. It was a bit overwhelming with the “resource village” filled with booths with everything from Yad Vashem to help getting Polish citizenship. I found Albee and I told him all about our visit to Sochocin.

Szymon really wanted Albee to visit that afternoon/night but he was exhausted from the travel. In the end, he decided to drive to Sochocin and I joined him. It was his first time seeing the renovated cemetery. As we were driving in Sochocin, Albee pointed to a building and said that was where his grandmother had a restaurant. He casually added that the restaurant had a pool table, the only place in town with one. That was where my grandfather would play pool on Saturday nights.

We met Szymon and quickly drove to the cemetery because it was starting to get dark.

I was glad I was able to be there when Albee saw the memorials that he had created for the first time. It was very moving. They plan on doing more work to the cemetery.

Albee told me that when he went back a few days later, he was at the cemetery for about two hours searching for pieces of tombstones and he actually found three! He marked them in a certain way that he’ll be able to find them again and wants to work on finding more.

When Albee visited Sochocin for the first time in the mid 80’s, he was looking for old people in the town who would remember Jews. He went to a woman’s house and when the woman saw him she started screaming his father’s name, “Icek, Icek!”. This woman had worked for his father. Albee’s father was in the button packaging business. Years later, when he told Lidia, a Sochocin native, the story and showed her the house where it happened, she said that she had grown up next to that house and they were her babysitters.

On our visit, Albee told Szymon this story for the first time and showed him the house and Szymon said “that was my aunt”. This woman was his mother’s younger sister.

When Albee returned after that first trip to Sochocin and told his father about the woman, his father kept talking about the Lejkowski family and spoke about one man who was a postman and spoke Yiddish and he couldn’t say enough good things about him. Albee told me this on the way to Plonsk (Szymon wanted to show us something there) and I remembered that Zbigniew mentioned that his father spoke Yiddish so I bet Albee that this man was their father. We got out of the car in Plonsk and he asked Szymon what his father did and he said he was in the button business. So he asked him if there was anyone in his family who was a postman and Szymon said that his father was a postman before he worked in buttons. It all started to make sense. We couldn’t understand why a Gentile Pole with no connection to Jews would work so hard to show us our family histories and to help with the cemetery and just put in so much of his own time to help us. We felt like there had to be some ulterior motive for all this but there wasn’t. We realized that Szymon was raised with an understanding and a love for the “other” and appreciation for Jews.

Szymon took us to Plonsk to see the Plonsk cemetery. The Plonsk cemetery does not exist anymore, it is now a shopping center. He brought us there to prove a point, to show that he does not want this to happen to the cemetery in Sochocin.

A few years ago, Lidia asked Albee to speak to her students about Israel and how there used to be Jews in Sochocin. When he was leaving the school, there was a huge slab with about 200 names of people that never returned home after World War II and he said to Lidia that there were also a lot of Jews that never returned home but he doesn’t see a single Jewish name on the list. She said that until he mentioned it, she had never thought about it. Albee told Szymon that when he spoke to the students and told them that there was a time where there was a sizable Jewish population in Sochocin, they had no idea and looked at him like he was crazy. Szymon said “of course, but they are not elite, they are simple people.” So I said to him, straight out, “I’m assuming that these kids are learning the history of their town and then there’s no mention that a major population of the town used to be Jews and aren’t there anymore? Are they not taught that?” There was no answer. The answer is that they aren’t taught that. And for me, that’s pretty scary because anti-Semitism is more prevalent with uneducated people. So if Szymon is saying that these kids don’t know anything because they are “simple people” and they’re not taught it in school, Jews are foreign to them. We become the “other,” and that’s very dangerous.

Szymon told Albee that he thinks they should put another fence around the cemetery walls because he’s nervous about vandalism. I found that interesting because it didn’t seem like he thought it would be anti-Semitic vandalism but Albee and I agreed that we’re pretty sure no one would vandalize a Christian cemetery.

It was already really late and we still had an hour drive so we said goodbye to Szymon and headed back to Warsaw. In the car we called my dad and put him on speaker to tell him about the visit.

Conference

I won’t write entries for the rest of the conference week because it wasn’t as eventful. I spent two days running around Warsaw visiting different archives with a translator. We didn’t find anything of real importance but I did gain a major disdain for Cyrillic writing. Records from 1868 until 1918 were in Russian (Cyrillic) and it is a very frustrating alphabet.

On Tuesday I went to the main archives in Warsaw’s Old Town with Daniel Wagner and a translator. Daniel’s mother was a Krell and he has put together two Krell family trees. One is a huge tree that includes my family. The other tree only goes as far back as Daniel’s great-grandfather. He has spent 20 years trying to connect these two trees and has not yet succeeded. Thanks to his research and the bigger Krell family tree, I discovered many familial connections.

I found the marriage record of Josef Menachem Krell’s parents (my grandmother’s first husband’s parents). I’m pretty sure I’ve seen this record before so it wasn’t too exciting. There was no mention of them being uncle and niece, which I had figured out through Daniel’s family tree. Daniel didn’t find anything either. Marek, my translator, and I left Daniel to keep searching and we ran to Warsaw’s civil registry before it closed.

There was nothing there either. It felt like a wild goose chase around Warsaw.

The next day I went with Marek to the archives at Warsaw University, which holds all Warsaw records (birth, marriage and death) from the past 100 years. Poland has very strict privacy laws because they are scared of Jews coming to reclaim pre-war property therefore records earlier than 100 years (from 1918 to present day) are not public. I believe that they just changed some of their privacy laws so marriage and death records older than 80 years are available but birth records still remain at 100 years. I got very nervous that they wouldn’t let me search for my family if I couldn’t prove a direct connection so I had my dad send me pictures of my birth certificate (which lists my father’s name), my father’s birth certificate (which lists his mother’s name) and my grandmother’s death certificate (which lists her parents’ names). That way I could prove my direct connection to the Gesundheits. I also had a copy of my grandmother’s pre-war marriage license to Josef Menachem Krell in order to prove my connection to Krell. In the end, they didn’t ask me to prove any connection so none of that was necessary.

The clerk was very nice and we filled out two forms. One form searching for the record of the birth of my grandmother’s son with Josef Menachem Krell and we included all known Warsaw addresses. The other form was to search for birth records of children born to Blima Gesundheit and Izrail Menasze Steinkritz (written as Sztajnkrec on their marriage record) between 1934 and 1940. My grandmother told us that her sister Blima had two children, a boy and a girl and that Blima had been pregnant when she came back to Poland from Palestine around 1934. We submitted the forms and the clerk said that it may take some time but they will email me if they find anything. I returned back to the conference for a little while and flew back to Israel that night.

I received an email about a month later from the Archives. They listed me all the different places that I had to email to ask for the records because they didn’t have anything. The wild goose chase continues.